The Rooster's Title Could Be Good for Brazilian Football

Atlético Mineiro is one of the great clubs in Brazil. His fanatical crowd, made up of approximately 7 million people, never leaves him. Titles, which are not details, end up becoming, paradoxically, for her, details: because passion is unconditional.

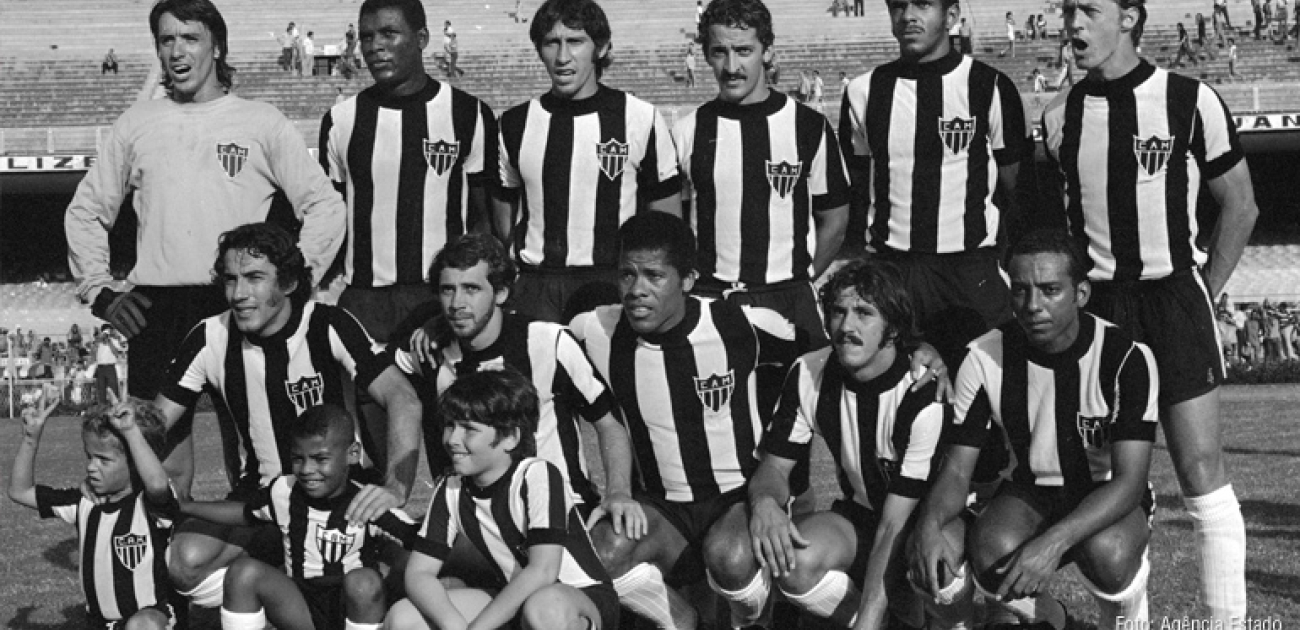

Since 1971, the year in which he became champion - and the first champion - Brazilian, he has suffered an (almost) inexplicable drought. It is true that he raised many other cups, including the most important of all, the Libertadores da América. Even so, its history lacked a re-encounter with success at the national level. Looks like the time has come at last.

Understanding the title's anatomy will be good, not only for the future of the team, but also for the future of football in Brazil. This is because the sporting result that will be achieved, even in the face of an acute financial crisis, does not result from chance - much less expresses a victory for associations.

I will not venture into the political history of the club. Neither of recent movements, with the emergence of important patrons. Far from it.

The focus will be on the set of factors, in the eyes of an outside spectator, which made the rise in football possible.

In fact, Atlético's numbers at the beginning of the year, based on the 2020 financial statements, affected by the pandemic, were frightening: billionaire debt on the rise; and falling revenues (in addition to being incompatible with the size of the team and its fans, as well as with the size of the debt). Through the associative logic, which is revealed in practically all other clubs, chaos was announced - and, with it, another year of waiting.

No matter how qualified its current leaders are - from what one hears, they really are -, the problem would not be resolved, as it has not been resolved, without the emergence of exogenous factors, which, incidentally, began to be introduced some time ago .

It is known that, in football, certain market maxims may eventually not work the way they do business. Millionaire teams and teams made up of big stars also fail; on the other hand, more modest organizations "fit" formations that reveal themselves and surprise everyone. It's true, but they don't usually support themselves. These experiences must be contextualized and, almost always, treated as accidents. Take, for example, the unlikely Premier League title won by Leicester in the 2015/2016 season.

The reality is that football has established itself, in the last 30 years, as a business with global projection. A different business, it's true, because it involves passion. More than that: because, being business and sport, at the same time, it deals with the transcendental element. There is no poet, I think, who has so far managed to transform the feeling of a goal into words. Or a title.

Well then. The combination of these factors indicates the complexity of the football company's environment, which, until the advent of the Rodrigo Pacheco Law (or SAF Law), had been avoided and fought in Brazil with almost every force.

The fight, mostly in the name of preserving a political and self-interested state of affairs, dissociated from the collective interest, thus explains the decadence and weakening of Brazilian clubs. Remember: while here there was a struggle for the monopoly of associativism, other countries found solutions to systemic problems - and their teams, alone, to overcome their own ills.

The cultural change, which the SAF Law should encourage, is beginning to be felt and heard. Certain clubs, such as Cruzeiro and Botafogo, announced the hiring of financial institutions to support their restructuring. Athletico Paranaense indicates that it wants to make the first IPO in history. Finally, the legal instruments emerged to form a thriving environment in Brazil.

Galo has not gone through, at least for the time being, the necessary transformational process, made possible by the SAF Law; but it indicated, for those who want to see (or even those who want to deny the reality), that there is only one way to maintain a team at the top: planning, management and, above all, access to capital.

For now, and despite the efforts being made under the club environment, the fundamental element for the title was one: capital.

Indeed, without the financial flow enabling (regardless of the form adopted) the hiring of some of the best South American players, the title, once again, would not have arrived. Such players made a difference.

However, the adopted model is not sustainable. And much less replicable. There is only one Menin family in Brazil and they are just Atletico devotees.

The family itself and other important investors who participated in the team's success, as well as the Atleticans, know that, for the project to be perpetuated, the other elements of the tripod must be formed; and this will only occur under the structure of the SAF - which will eventually make it possible for any and all fans to become, in fact and by right, a shareholder, or owner, of their team at heart.

The success of patronage may thus lead to a greater movement, conducive to a necessary and beneficial structural transformation.

At the same time, the other Brazilian teams, which faced, throughout the year, a squad that will make history, must also have realized that, whether under the intensification of patronage or under the model of a future SAF, they will have very, very difficult face the Galo, if they do not find the means to finance their own activities and build great casts.

Perhaps, for these reasons, the title of Atlético can transform not only the legal form of football practice entities and access to capitals, but, in particular, the mentality and sense of urgency of the structural reformulation of the football activity Brazil.

Do you want more information?

Rodrigo Monteiro de Castro

Rodrigo Monteiro de CastroRodrigo Monteiro de Castro is specialized in corporate and business laws, corporate transactions (M&A), capital markets and contracts.